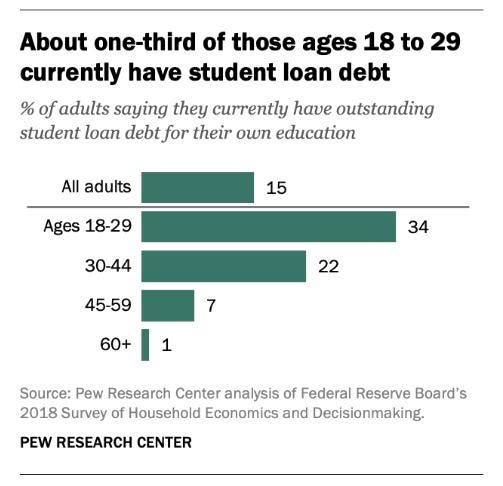

Over the past 12 times, US student loan debt has quadrupled to a astounding $1.7 trillion. Nearly 44 million Americans carry an average debt of $37, 718, and over 11 percent of aggregate student loan debt (pre- COVID) is more than 90 days delinquent.

This past year, the common public school student borrowed over $32, 000 to obtain a bachelor’s degree. But, only 11 percent of employers believe that a diploma prepares students for the workforce. It’s a cruel irony: a $32, 000 loan – not counting interest – for a degree that doesn’t prepare you for the career needed to repay the debt.

Tracing the Foundations

Federal student loans were first offered in 1958 under the National Defense Education Act ( NDEA ) to promote specific academic majors—engineering, science, or education —in response to the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik. The Higher Education Act of 1965 ( HEA ), which extended NDEA applicability to all majors, was passed seven years later as a result of President Johnson’s declaration that higher education was no longer a luxury but a necessity.

In 1992, Congress reauthorized HEA, giving fresh, unsubsidized student loans to any student regardless of financial have, in spite of an earlier Senate review finding the student loan system riddled with waste, fraud, and abuse. Three years later, Congress authorized the US Treasury to issue student loans instantly, and student loan debt increased to $187 billion.

In higher education, restoring financial education

Fast forward to today, and the current $1.7 trillion debt. Market forces increased the rising cost of tuition while putting pressure on everyone to get a college degree, all without consideration for the ultimate success of the work, i .e. a well-paying work, was removed by extending and expanding the system and removing the financial seal on loans.

In other words, there’s full petit understanding of loan with no evaluation of risk. As any economist—or anyone who has a record score—can tell you, this is not how funds markets function.

Good credit markets are essential to a strong business because they enable it to assess risk and direct capital investment in the areas where it is most likely to succeed. This is called risk- based sales, which means lower costs of capital—that is, cheaper loans—for lower- chance investments and higher saving costs for extended- shot ideas. According to that principle, lenders determine threat on everything from mortgages to credit cards to auto loans.

But, that’s not the scenario for federal student loans. One of the few record instruments in the world that does not consider risk is federal student loans. We don’t consider the likelihood of graduation or the underlying value of a degree. Interest costs are fixed, set lower than their personal counterparts. Federally supported student loans provide a standard credit sales model that deliberately bias opportunities by lowering real-market interest costs.

Imagine that 50% of graduates from a certain key made student debts defaults. In such a case, personal lenders may charge loans with up to 30% interest, which would give rise to a degree of risk that may inspire students to reconsider their field of study.

Otherwise, government intervention skewed incentives for post-secondary institutions, and the degree’s core value was skewed from the financial viability of paying back one’s loan.

Degrees from colleges are no access to the middle class. In fact, a wider middle class was making a greater share of the total US money than we see today in 1971, when much fewer Americans were college-educated. We created a shortage of skilled craftsmen and a glut of university graduates with degrees that businesses consider of little value by labeling them as “necessary” for victory.

We mayn’t ending all federal student loans, we need a system to support lower- income loans. However, we also need to reevaluate the pipeline from high school to university and encourage students to research the numerous post-secondary options that don’t demand $40,000 in debt.

The Bottom Line

More than just blaming loans for student loans, there will be ways to fix this mess. In theory, income-driven payment plans seem appealing, but many Americans are still unable to pay their college loan. And erasing outstanding accounts without treating the illness is useless.

Restoring economic education within higher education institutions is essential to addressing the scholar mortgage crisis. The single green lengthy- term solution is restoring complimentary markets, limiting government intervention, and holding post- extra institutions accountable for their students’ outcomes.

If individuals are able to evaluate the benefits and drawbacks of a university degree, more pupils may start to inquire, “Do I really need to go to school?”