What happened?

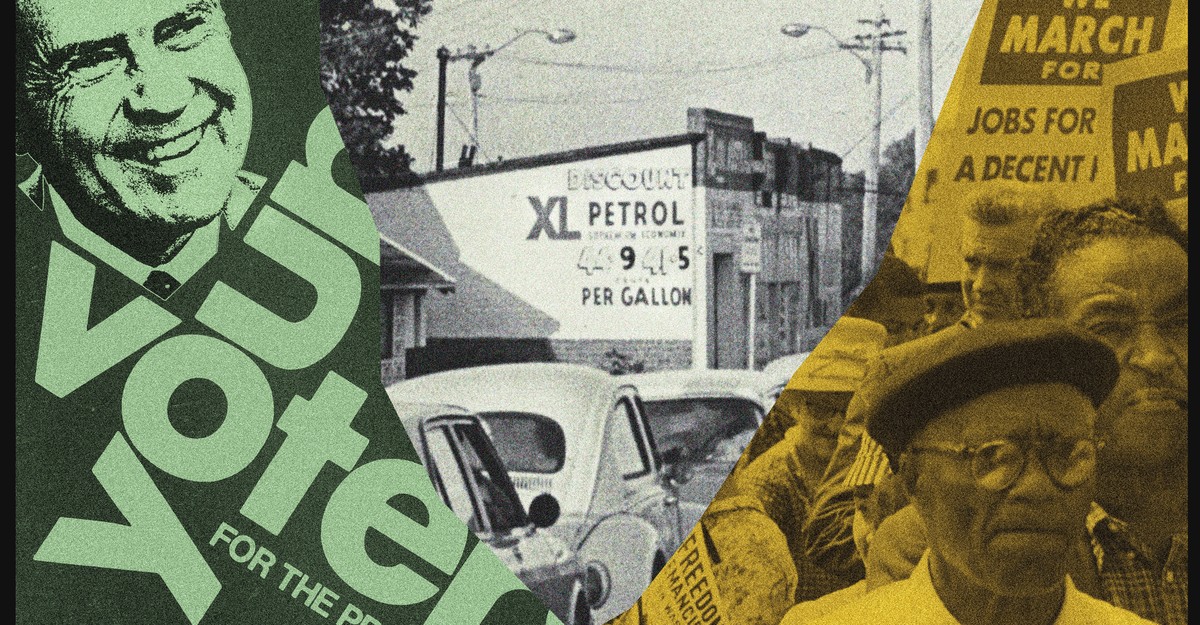

One explanation is that American voters abandoned the program that served their forebears. U.S. laws and policies were shaped from the 1940s to the 1970s, known as the “New Deal era,” to ensure robust unionization, high taxes on the wealthy, substantial public investments, and an expanding social safety net. As the economy grew, inequality decreased. However, by that time, the economy was faltering, and voters began to reject the post-war compromise. When Ronald Reagan took office, he pledged to stimulate economic growth by cutting taxes on the wealthy and corporations, deregulating businesses, and enforcing competitive regulations. It was believed that a rising tide would lift all boats. Instead, living standards stagnated, life expectancy lagged behind that of comparable nations, and inequality increased. No other advanced market experienced a sharper reversal in wealth, freedom, and public well-being trends than the United States. It also transitioned to free-market economics more rapidly than any other developed economy. A child born in Norway or the UK now has a much better chance of outearning their parents than one born in the United States.

This story has garnered significant media attention. However, a puzzle remains: Why did America vehemently reject the New Deal? And why did so many politicians and voters embrace the free-market compromise that replaced it?

In an effort to understand the rise of Donald Trump, who declared in 2015 that “The American dream is dead,” and the tumultuous upheaval in American society, policymakers, academics, and journalists have been scrambling for answers to these questions since 2016. There are now three key theories, each explaining how we got here and what might happen if we change our course. According to one theory, the story primarily revolves around the backlash against civil rights legislation. Another theory places more blame on the cultural elitism of the Democratic Party. The third theory focuses on the challenges posed by uncontrollable global issues. Each idea is incomplete on its own. Together, they contribute significantly to understanding the political and economic uncertainty we are witnessing.

In her 2021 book, “The Sum of Us,” Heather McGhee, former leader of the think tank Demos, writes that “the American landscape once featured magnificent public swimming pools, some large enough to hold hundreds of swimmers at a time.” However, in many places, there were separate pools for white Americans. Segregation followed. White communities chose to close the pools for everyone rather than open them to their Black counterparts. This, in McGhee’s view, is a microcosm of how America’s political economy has changed over the past 50 years: White Americans preferred to withhold shared resources from Black Americans rather than significantly improve their own lives.

Democrats dominated national politics from the 1930s until the late 1960s. They transformed the American economy by leveraging their power to enact broad progressive legislation. However, after President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, their coalition, which included Northern Democrats and Southern Dixiecrats, began to fracture. This rift was exploited by Richard Nixon’s “Southern strategy,” which reshaped the political map. Since then, no Democratic presidential candidate has won a majority of the white vote.

Importantly, the civil rights movement also altered the economic outlook of white Americans. In 1956, 65 percent of white people believed the government should provide a maximum standard of living and guarantee work for anyone who wanted it. By 1964, that percentage had dropped to 35 percent. Ronald Reagan eventually transformed this backlash by portraying high taxes and generous social programs as siphoning money from hardworking (white) Americans to undeserving (Black) “welfare queens.” This narrative resonated with voters and helped turn the tide towards a free-market message. This story, popular on the left, portrays Democrats as tragic heroes who paid a price for doing what was right on social issues: economic inequality.

David Leonhardt, a columnist for The New York Times, is less inclined to absolve progressives of responsibility. According to his recent book, “The Past Was the Shining Future,” the dissolution of the New Deal coalition involved more than just cultural issues. The left was deeply rooted in a powerful working-class movement centered on material interests throughout the 1950s. However, a New Left dominated by affluent university students emerged in the early 1960s. These activists prioritized issues such as nuclear disarmament, children’s rights, and the Vietnam War over economic concerns. Their tactics involved civil disobedience and protests, rather than the politics of governance. Leonhardt argues that the rise of the New Left hastened the departure of white working-class voters from the Democratic coalition.

In this narrative, Robert F. Kennedy emerges as an unlikely warrior. Kennedy staunchly supported civil rights, but he recognized that Democrats were alienating their working-class base. He took aim at the New Left, opposing tax deductions for college students and emphasizing the need to restore “law and order” as a presidential candidate in 1968. Kennedy received criticism from the liberal press for these and other moderate positions, yet he garnered support from both white and Black working-class voters, helping him win crucial primary elections.

However, Kennedy was assassinated in June of that year, taking with him the social agenda he stood for. Republican Nixon won the White House that November. He arrived at the same conclusion as Kennedy, that millions of voters were at risk because the Democrats had lost touch with the working class. Nixon portrayed George McGovern as the “three A’s” candidate for the 1972 election—acid, abortion, and amnesty (referring to draft dodgers). He accused Democrats of being soft on crime and immoral. Nixon won a landslide victory on Election Day, marking the turning point in the New Deal coalition. From that point onward, the Democratic Party would continue to lose working-class voters as it increasingly represented the views of college graduates and professionals.

The accounts of McGhee and Leonhardt may appear at odds, echoing the “race versus class” debate that unfolded after Trump’s victory in 2016. However, they actually complement each other. Left-leaning parties in most European nations, not just the United States, have lost support from working-class voters and become dominated by college-educated voters since the 1960s, as economist Thomas Piketty has shown. While the U.S. has a distinct racial history, one of the main differences between Europe and the United States, somewhere in Europe experienced a backlash as swift and potent as that of the United States.

Although the Democratic coalition may have fractured after the 1972 election, this doesn’t explain the rise of free-market conservatism. The fresh Republican majority didn’t present a radical economic agenda. Nixon combined New Deal economics with social conservatism. His presidency increased the capital gains tax, established the Environmental Protection Agency, and expanded funding for Social Security and food stamps. Laissez-faire economics were still unpopular at the time. Polls from the 1970s showed that a majority of Republicans believed that income and benefits should be maintained at current levels, and anti-tax ballot initiatives in several states were soundly defeated. Even Reagan largely avoided discussing tax cuts during his unsuccessful presidential campaign in 1976. There is still a gap in the narrative of America’s economic upheaval.

“The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order,” written in 2022 by economic scholar Gary Gerstle, describes that period as a severe economic crisis in the mid-’70s. The 1973 oil embargo caused inflation to spiral out of control. The economy soon entered a recession. After adjusting for inflation, median family income was significantly lower in 1979 than at the beginning of the century. According to Gerstle, “These shifting economic conditions, following the divisions over race and Vietnam, ruptured the New Deal order.” (Leonhardt also discusses the economic shocks of the 1970s, though they are less central to his analysis.)

For decades, a small group of academics and business figures had been promoting free-market ideas, most notably University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman. Reagan was the ideal messenger, and the troubles of the 1970s provided an opportune moment to translate them into public policy. In his 1981 inaugural address, he famously declared that “government is not the solution to our problem. Government is the problem.”

Reagan’s genius lay in the fact that his message had different meanings for different constituencies. For white Southerners, the government enforced school desegregation. For the religious right, the government permitted abortion and prohibited prayer in schools. Additionally, a bloated federal government was seen as responsible for the declining economic well-being of working-class citizens who embraced Reagan’s campaign. Reagan’s rhetoric also highlighted real flaws in the existing state of the economy. Nixon’s attempt at wage and price controls had failed to contain inflation, which had been ignited by the Johnson administration and its high spending. American manufacturers struggled to compete with non-unionized Chinese counterparts due to the generous contracts won by auto unions. After a painful decade, most Americans supported tax cuts. The public was yearning for change.

They got what they wished for. When Reagan took office, the top marginal income tax rate was 70 percent, and by the time he left, it had been reduced to 28 percent. The coalition grew smaller. The financial industry prospered due to deregulation, and Reagan’s appointments to the Supreme Court paved the way for a series of pro-business decisions in the years to come. Gerstle argues that none of this was preordained. The social upheaval of the 1960s contributed to the dissolution of the Democratic coalition, but it took the unusual combination of a severe economic crisis and a skilled political communicator to gain traction. Democrats had embraced the tenets of the Reagan era by the 1990s. In addition to pushing through the North American Free Trade Agreement and signing a welfare reform bill, President Bill Clinton further deregulated the financial sector. In his 1996 State of the Union speech, Clinton proclaimed that “the era of big government is over,” echoing Reagan.

Another political moment that resembles the 1960s and 1970s in some ways appears to be unfolding in America today. Then and now, longstanding coalitions splintered, new issues arose, and policies that were once seen as radical became mainstream. Leaders from both major parties now face the same challenge of reconciling themselves to a smaller government and freer markets. However, the present moment is marked by a sense of tumultuous upheaval, much like the 1970s. A new economic debate has yet to replace many outdated ideas, even though many of them have lost their appeal. A new order has yet to emerge, but the old one is unraveling.

The Biden administration and its supporters are attempting to change this. President Joe Biden has pursued an ambitious policy agenda since taking office, aiming to reshape the U.S. economy and openly challenging Reagan’s legacy. In 2020, Biden remarked, “Milton Friedman isn’t running the show anymore.” However, the social coalition that supports an economic model determines its strength. Unlike Nixon, Biden has not figured out how to fracture the coalition of his opponents. Furthermore, he has not crafted the kind of compelling political narrative needed to forge a new one, as Reagan did. Recent polls suggest that he may struggle to secure re-election.

The Republican Party is currently grappling with a lack of a clear economic agenda. A few Democratic senators, including Josh Hawley, Marco Rubio, and J.D. Vance, have expressed some support for economic populism, but they remain a minority within their party.

It is challenging to envision how we will transition from our turbulent present to a new political and economic consensus. But transitional moments have always been like this. Just as no one could have foreseen the dawn of a new economic era in the early 1970s due to social upheaval, economic crisis, and political talent, perhaps the same is true today. The Reagan era will not return. The New Deal experiment that preceded it is also inadequate. The next chapter may indeed be something entirely new.

We get paid when you purchase a book using one of the links on this site. I appreciate you supporting The Atlantic.